There’s a question many parents ask when their student heads off to college: how much money should I give them each month?

Too much, and they never learn the value of a dollar. Too little, and they’re stressed instead of studying. The right number isn’t one-size-fits-all, but there is a right way to frame it: make it a monthly Money Game™.

The Money Game™ is a real project that my firm, Cove Wealth Management, offers our clients and their children to “play” by using real money to build financial habits and accelerate financial learning. You can do something similar with your students while they are in college and still under your care, but outside your home.

Just like athletes scrimmage before the real game, your student can scrimmage with money in college, under your guidance as their financial coach. The stakes are real, but manageable, and the lessons last long after the degree.

Setting a baseline

Start with a simple budget that covers the basics: food beyond the meal plan, transportation, and a few extras. For many families, that falls in the range of $200–$400 per month. Some students with cars or off-campus housing may need more, others less. The point isn’t the number, but rather giving your student consistent responsibility and asking them to track what comes in and what goes out on a monthly basis.

So to get started, pick a baseline, agree on it, and stick with it. Then, treat it as their “salary” for managing their own small household economy.

Making it a game

Frame each month as a round of the Money Game. Their challenge:

- Plan: Write down expected expenses for the month.

- Play: Spend and save within the budget.

- Report: Share with you at the end of the month how it went.

This isn’t about you micromanaging receipts. It’s about helping them reflect: Where did the money go? Did they come out ahead or behind? What surprised them?

You can even add in a “bonus incentive.” For example, if they end the month with $50 left over, you’ll match half of it into a savings account for a designated purpose.

Real months, real choices

Take October. Between football tickets, coffee runs, and a Halloween costume, costs can creep up. Challenge your student to plan ahead. If they know October will be heavier, perhaps September needs to be leaner.

Or take December, the classic “big spend” month. Students often want to buy gifts for family and friends or travel home. That’s a perfect chance to talk about prioritizing: What do you want to give? What will it cost? How can you spread those expenses over several months so December doesn’t break the bank?

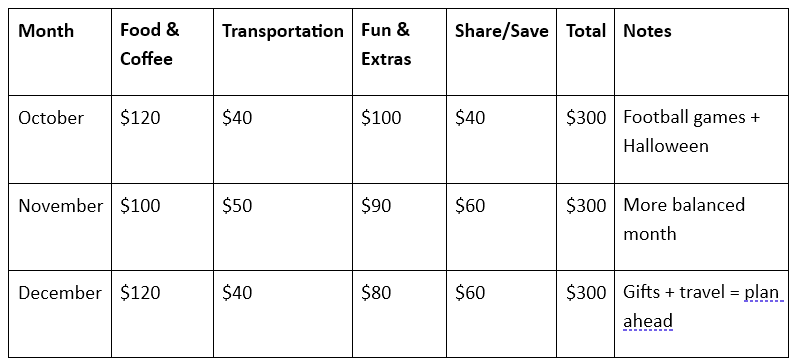

Here’s a simple snapshot of what three different months might look like for a student working with a $300 baseline allowance:

Baseline Allowance Chart

These numbers are only examples, but the exercise helps students think in categories rather than random swipes of a debit card.

A financial framework: share, save, spend

The Money Game works best when it’s not just about surviving the month but about shaping habits. A simple financial framework of share, save, spend works for young adults as well as it does for older adults.

- Share: Encourage your student to set aside even a small portion, perhaps about 10% of their monthly allotment, to give away. Whether they give to a campus cause, a friend’s fundraiser, or their home church, sharing develops perspective, gratitude, and generosity.

- Save: Build in a savings category for bigger goals. Maybe they want to buy a nicer laptop, fund a spring break trip, or just build a rainy-day cushion. Saving isn’t glamorous, but it’s empowering to see how these small, consistent habits stack up.

- Spend: Let them enjoy the rest guilt-free. College is stressful enough, and they need money for fun with friends, too.

This three-part framework turns money from a stressor into a tool. It reminds students that every dollar carries a choice.

The long game

Parents sometimes hesitate to hand over money because they fear it’ll be wasted. Remember, however, that mistakes are part of the lesson. Overspending in October is better than overspending on a mortgage ten years from now.

Think of this monthly allowance not as a cost but as tuition for Financial Intelligence 101. You’re in the driver’s seat, coaching your student to budget, prioritize, and make trade-offs. Those are the same skills they’ll need when their paycheck is bigger and the stakes are higher.

Your first step of opening a 529 got them started on the road to college. The next step of giving them a baseline allowance to manage sets them on the path to financial success in adulthood.

And like every game, the more they practice, the better they’ll play. Let’s go!

4772233